Île de Sein

Île de Sein receives the Cross of Liberation on January 1. In June 1940, almost all of the men of fighting age chose to join the Free French Forces in England.

Blason de l’Ile de Sein

Blason de l’Ile de Sein

The small island of Île de Sein (56 hectares) is located in Brittany, off the Pointe du Raz, and had 1,400 inhabitants in September 1939. The large majority of its men were mobilized, while a small garrison of around twenty men was set up on the island.

In June 1940, in addition to the aerial combats taking place above their heads, the island’s inhabitants received information from the boats that docked there as well as via the few battery-powered wireless radios and crystal sets on the island which did not have any electricity.

This is how the islanders found out about the Capture of Rennes and the evacuation of Brest on June 19. On the same day, Ar Zénith, which transported passengers, goods and mail twice weekly between Audierne and Île de Sein, docked on the island. It was carrying around one hundred alpine troops, young men from Audierne, and war equipment that it was required to take to Ouessant. It left the island at around 7 pm with the soldiers only, accompanied by the Velléda, a ship that supplied lighthouses, which took the civilians and islanders. But in reality, after a stopover in Ouessant, Ar Zénith was ordered to cross the channel by the military authorities and head to Plymouth; its four crew members were the first of the island’s inhabitants to leave for England.

Velléda returned to Île de Sein the following day and told the inhabitants what had happened. On June 21, Île de Sein’s garrison left. A few dozen islanders found out that a French general was due to speak on the radio in London. On June 22, they gathered round one of the island’s wireless radios and listened to General de Gaulle’s speech. Strongly impressed, they each returned home while planes bombed the cargo ships that passed offshore.

On June 24, the mayor displayed a notice containing information received from Audierne by telephone, which ordered the military to surrender to the German authorities in Audierne. In reaction to the threat of being taken prisoner, Jean-Marie Porsmoguer and Prosper Couillandre took it upon themselves to arm their respective ships, the Velléda and Rouanez-ar-Mor. By 9 pm, both boats were fully loaded with men of fighting age.

On June 25, a boat from the island sailed to the continent where a notice stated that all men aged 18 to 60 were required to make themselves available to the occupation’s forces. This new threat came with a new response: the next day, two more boats left the island: Rouanez-ar-Péoc'h belonging to François Fouquet, and Maris Stella belonging to Martin Guilcher. Pierre Couillandre’s Corbeau des mers and its passengers followed shortly after. Like the day before, the mayor and rector (parish priest) supervised the departures; islanders aged 15 and under were not allowed to leave.

As such, from June 24-26, 114 islanders, who had not previously been mobilized due to their age or family responsibilities, left Île de Sein. Others arrived in England by various means at a later date. In total, 128 of the island’s inhabitants left for Great Britain; the oldest was 54 and the youngest was 14. In early July, those who headed to England were assembled with three hundred other volunteers at Olympia Hall in London, where General de Gaulle inspected them. Shaking the hand of every one of them and asking where they had come from, the leader of the Free French was extremely surprised, reportedly exclaiming “So it seems Île de Sein is a quarter of France!”.

Île de Sein inhabitants then received various postings in line with their age and specialisms; the majority were sent to the Free French Naval Forces and initially served on the Courbet. The oldest inhabitants were assigned to the Fisheries Department in Penzance and the Free France merchant navy, and took part in providing England with supplies. Twenty-two of them died for France.

The Germans arrived on the island in early July 1940, before establishing a small infantry garrison and maritime customs post (GAST) there, which exercised control over fishing boats. They also planted mines and put up barbed wire. Extremely strict regulations were applied to traffic both on the island and in the sea; those who were given travel documents and temporary authorizations to leave did so on the understanding that their families were the guarantors of their return.

Monument de l’Ile de Sein en hommage aux Sénans

Monument de l’Ile de Sein en hommage aux Sénans

Ile de Sein islanders, the majority of which were women, children and the elderly, were subjected to particularly difficult conditions in terms of supplies due to the departure of the island’s men, resulting in a lack of income and fishing produce. Malnutrition affected the population for the duration of the occupation, which was estimated at 273 inhabitants in a 1943 census, demonstrating great solidarity.

As such, the rector of Île de Sein set up a school canteen for boys whose fathers had left for England. Mayor Louis Guilcher, who was forced to liaise with the occupier, tried his best to improve the living conditions of his fellow citizens.

The island's only income was from the sale of salt. On May 1, 1943, staying loyal to the traditions of rescuers from Île de Sein, after witnessing aerial combat above Ouessant, sailors on the Pax Vobis sloop went to help three pilots from an American bomber that had crashed into the sea and took them onto the island. In a unique example, a German reconnaissance plane landed on Île de Sein to take back one of the three wounded men who was considered unable to travel by boat.

The liberation finally took place on August 4, 1944 marked by the departure of the German garrison who blew up the island’s lighthouse before it left. On August 30, 1946, General de Gaulle went to Île de Sein and presented it with the Cross of Liberation during a simple and moving ceremony.

As President of the Republic, he returned a second time on September 7, 1960 to inaugurate the Free French Forces Monument which featured the Breton motto “Kentoc'h Mervel”, meaning “Rather die”, alongside the citation “Le soldat qui ne se reconnaît pas vaincu a toujours raison”, meaning “The soldier who does not proclaim himself defeated is always right.” Île de Sein is the most decorated French commune with regards to the Second World War.

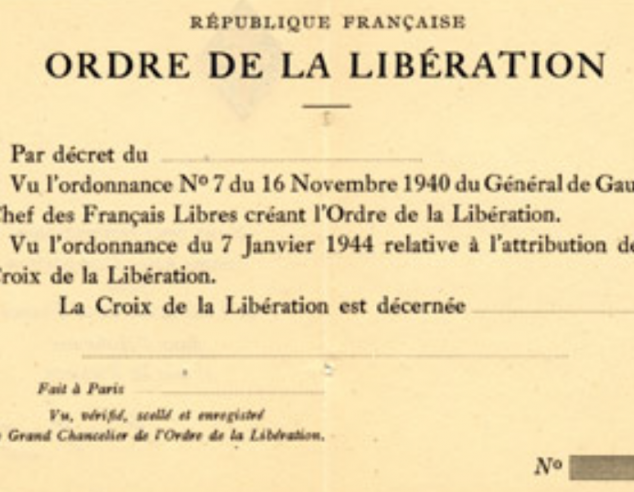

- Companion of the Liberation - Decree of January 1, 1946

- Croix de Guerre 1939-1945

- French Resistance Medal with rosette

Remise de la Croix de la Libération à l’Ile de Sein par le général de Gaulle en août 1946

Remise de la Croix de la Libération à l’Ile de Sein par le général de Gaulle en août 1946

General de Gaulle did not make a speech when he awarded the Cross of Liberation to Île de Sein, but he did address its inhabitants on two separate occasions.

“From now on, there will always be people in France who will think of Île de Sein. The whole of France will know that there was a good and courageous island off the Breton coast, whose magnificent example will become legendary. Children will learn about the heroic actions of a good and courageous French island in their history books” then, to the crowd, after presenting the cross, “You saved France. We must never forget that. France is slowly picking itself back up. It is immortal, it will outlive us all.”

“Faced with enemy invasion, it refused to abandon its battlefield: the sea. It sent all of its children to fight under the flag of Free France, thus becoming the example and the symbol of the whole of Brittany.” (Ile de Sein, Companion of the Liberation by Decree of January 1, 1946)